The value of reanalysing historical data to model climate change has made scientific news again. An American project to digitise 1970s radar recordings reveals that the massive Thwaites Glacier in western Antarctica is melting faster than previously thought.

Closer to home, another kind of historical data – unique tidal records held in the National Archives’ Tasmania office – may help us track environmental change over the past two centuries.

Highs and lows: tracking sea levels in Tasmania

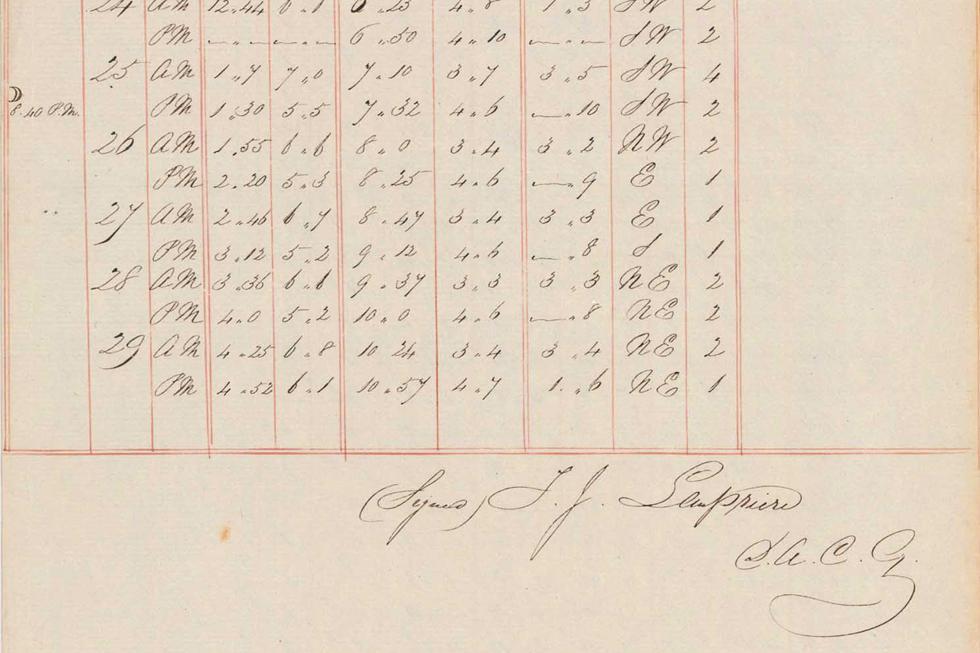

In mid-1837, the Deputy Assistant Commissary General at Port Arthur penal settlement began keeping a record of local tide levels.

Using his tide gauge on the shoreline, Thomas Lempriere collected data on high and low water every day until late 1842.

This keen amateur meteorologist sent the resulting records, a Register of Tides at Port Arthur, to the Royal Society in London via Sir John Franklin, Governor of Van Diemen’s Land. The tables that remained in Tasmania, spanning December 1839 and 1840–41, are among the oldest collections held by the National Archives.

On 1 July 1841, Lempriere worked with visiting explorer James Clark Ross to etch a line into the sandstone on the Isle of the Dead, lying just offshore from Port Arthur. Carved around an hour before high tide, this marker provides one of the earliest sea level measurements in the southern hemisphere. Together with Lempriere’s tidal data, it offers a means of tracking mean sea levels over the past two centuries.

Scientists comparing Lempriere’s recordings with current measurements estimate that the sea level at the Isle of the Dead rose by 13.5 centimetres from 1841 to 2000. This finding accords with long-term tide records from around the world, which suggest a mean 23-centimetre rise between 1880 and 2014.

Fragile records inform the future

A major challenge faced by researchers using historical scientific data is the records’ physical fragility.

The radar recordings recently analysed by US scientists, for example, were generated by aircraft flying above Antarctica, using ice-penetrating radar to map the landmass underneath. Instead of being saved as electronic data files, the radar screen displays were captured on 35-millimetre optical film.

The National Archives of Australia holds approximately 20,000 similar scientific data films. These films need specialist preservation to avoid the destructive ‘vinegar syndrome’, as well as careful handling through the digitisation process.

Lempriere’s historic tabulations were likewise at risk from two sources: the paper and the ink that he used. Conservators at the National Archives have recently cleaned and stabilised the fragile, 180-year-old paper.

They focused on minimising moisture to avoid chemically activating Lempriere’s ‘iron gall’ ink, which may otherwise have eaten through the paper. Kept in archival-quality sleeves, these globally significant records are now considered stable for long-term survival.

Meanwhile, scientists continue the task of sea-level monitoring that Thomas Lempriere pioneered nearly two centuries ago.